Last Window: The Secret of Cape West is the sequel to the Nintendo DS point and click game called Hotel Dusk. I’ve been playing it recently, as a result of finding it in a local store. This was fortunate: Last Window was never released in the United States, so it is difficult to find.

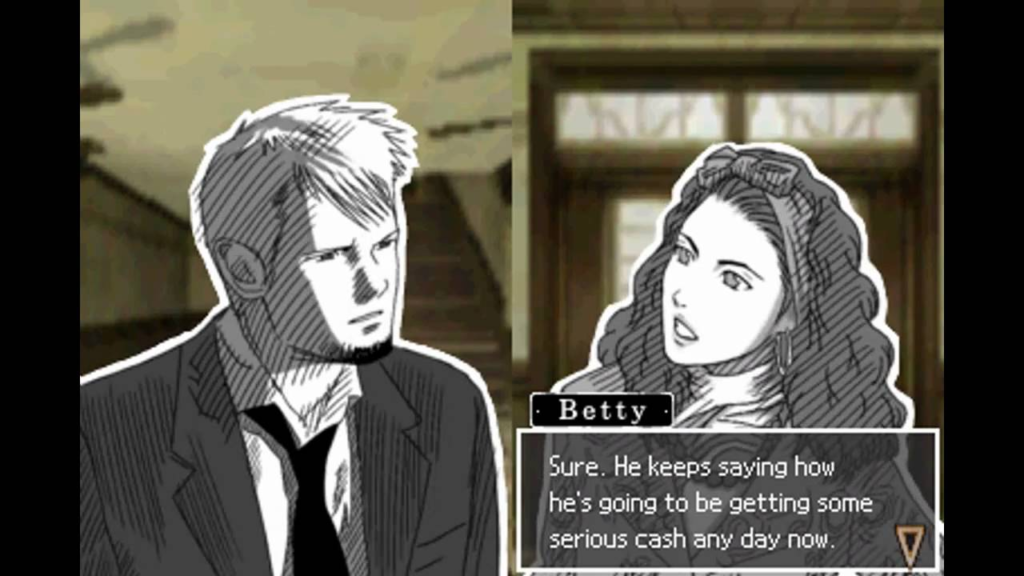

Like most games of this type, conversations with characters play a key role in the gameplay. Here is a typical gameplay flow example from Hotel Dusk:

- NPC talks to player, the player responds. There are no options. It is just dialog that the player advances through by pressing buttons.

- Sometimes, however, a key point is made by the NPC. When this happens, an exclamation point inside a triangle appears in the center. This means you are going to pressure the person you are talking to. You are given two dialog options to do this.

- The outcomes of your choices break down as follows: A: One option is correct, which simply means you get more information. The other option results in the character having a dark lighting affect pass over their character, giving you visual feedback that you are wrong. From here you are either redirected back to this point in the conversation, or a game over sequence occurs. It usually takes multiple incorrect responses in a conversation to trigger a game over. B: Sometimes both options are wrong. And the correct decision is to ignore the prompt and not pressure the character.

This mechanic of ignoring the prompt is actually an innovation in Last Window. Hotel Dusk has the same “press the witness!” mechanic, but I cannot recall a single instance where ignoring this was the correct decision. It rendered the mechanic a mere bit a window-dressing, an extra game interaction to simulate being a detective, but with no real consequence.

Knowing that ignoring the prompt to press for more information is sometimes the right choice gives some subtle depth to the gameplay that is definitely appreciated.

That said, Last Window still feels arbitrary with its conversation design. This is a problem common to games of this type. Even with the added mechanic of ignoring a line of questions, the game’s conversations have a “trial and error” feeling. Is this an unavoidable genre trope, or can this be done differently?

Let’s explore some different means of addressing this.

- Adding more dialog options. This is something Disaster Report 4 does, in that instead of two dialog choices you get many. This gives the impression of a more advanced system, but without some very complicated engineering to allow for all of those choices to be accounted for, a system like this usually ends up funneling down into that one right choice.

- Basing dialog success on statistics, not just a simple “right answer.” I can imagine the player character having a simple array of character statistics that govern personality attributes. As in real life, sometimes one’s willingness to respond to a person isn’t based on what that person is saying, but the personality of the person asking the question. In Last Window, certain characters often get upset and refuse to talk if you are aggressive. Perhaps different character attributes might actually make those choices correct, let’s say if you have a stat called persuasion or something of that sort. Usually this is accomplished not just by having a certain number threshold that automatically makes the dialog option correct, but rather via some kind of randomization that uses that number to govern the probability of success (a dice roll, basically). This solution works to make the right/wrong answers of a dialog less black-and-white. It would require more engineering, but these systems can be done pretty simply.

- Use of time as a game mechanic. In Jesse Schell’s The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, Schell discusses time as a mechanic, specifically discrete time versus continuous time. A game like Last Window is mostly discrete time: you have limitless time to make a dialog choice. Simply introducing a timer that forces failure upon you if you do not pick something quickly (continuous time) can add tension to conversation encounters. It also helps make the dialog choices more meaningful, since you have a limited time to think through the responses. This doesn’t necessarily solve the trial-and-error problem, but it at least makes the gameplay more dramatic, and does force to player to focus hard on their knowledge of the game’s story and characters.

Of these options, I prefer the second. Using simple statistics like this to alter gameplay outcomes leverages the strength of the computer as a gaming medium while giving the player some agency of the results that go beyond simply understanding the game writer’s intent perfectly. The game design would have to, of course, both communicate to the player what those attributes are, and a good design gives the player the means to manage these attributes (that is, they aren’t just static).

That said, it should also be remembered that simply asking the player to make deductive reasoning choices based on the game’s story is a valid game design choice as well, which is what these adventure games typically rely on. Perhaps no game I can think of does this better than the Phoenix Wright series, in that you aren’t just given a couple of dialog choices with the hopes that you can figure out the correct one. In those games, you get the option of reviewing evidence at any time, while certain key phrases are highlighted in color. In other works, Phoenix Wright gives you better access to information, so your judgements have a better chance at success. Hotel Dusk and Last Window tend to rely on your memory a little bit more.